Can blow star-forming gas 1000 light-years out of core region of host galaxies

Credits: ESA/ATG Medialab

Space news (astrophysics: evolution of galaxies; feedback mechanisms) – about 2.3 billion years ago in a galaxy far, far away and standing in a fierce, 2 million mile per hour (3 million kilometers per hour) outflow of star-forming gas –

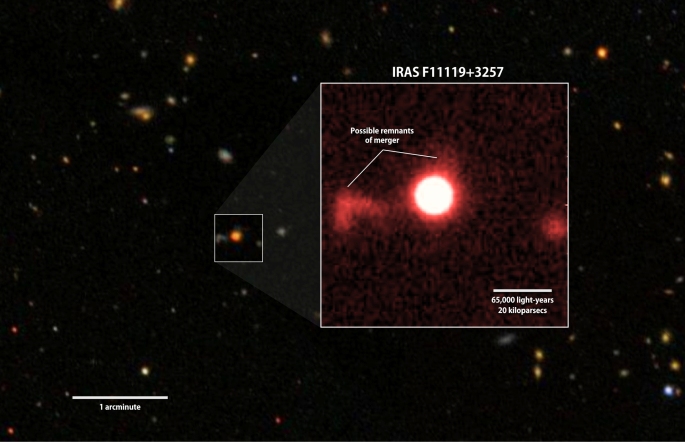

Astrophysicists studying the evolution of galaxies using the Suzaku X-ray satellite and the European Space Agency’s Herschel Infrared Space Observatory have found evidence suggesting supermassive black holes significantly influence the evolution of their host galaxies. They found data pointing to winds near a monster black hole blowing star-forming gas over 1,000 light-years from the galaxy center. Enough material to form around 800 stars with the mass of our own Sol.

“This is the first study directly connecting a galaxy’s actively ‘feeding’ black hole to features found at much larger physical scales,” said lead researcher Francesco Tombesi, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and the University of Maryland, College Park (UMCP). “We detect the wind arising from the luminous disk of gas very close to the black hole, and we show that it’s responsible for blowing star-forming gas out of the galaxy’s central regions.”

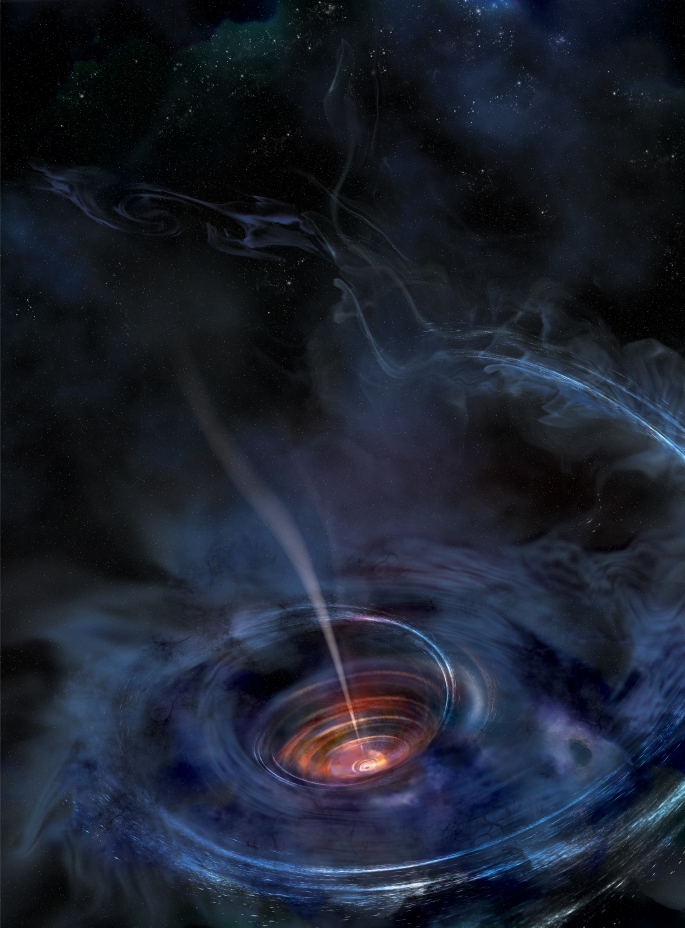

The artist’s view of galaxy IRAS F11119+3257 (F11119) above shows 3 million miles per hour winds produced near the supermassive black hole at its center heating and dispersing cold, dense molecular clouds that could form new stars. Astronomers believe these winds are part of a feedback mechanism that blows star-forming gas from galaxy centers, forever altering the structure and evolution of their host galaxy.

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/SDSS/S. Veilleux

Astronomers have been studying the Monster of the Milky Way, the supermassive black hole with an estimated mass six million times that of Sol thought to reside at the center of our galaxy, for years. The monster black hole at the core of F11119 is thought to contain around 16 million times the mass of Sol. The accretion disk surrounding this supermassive black hole is measured at hundreds of times the diameter of our solar system. The 170 million miles per hour (270 million kilometers per hour) winds emanating from its accretion disk push the star-forming dust out of the central regions of the galaxy. Producing a steady flow of cold gas over a thousand light-years across traveling at around 2 million mph (3 million kph) and moving a volume of mass equal to around 800 Suns.

Astrophysicists have been searching for clues to a possible correlation between the masses of a galaxy’s central supermassive black hole and its galactic bulge. They have observed galaxies with more massive black holes generally, have bulges with proportionately larger stellar mass. The steady flow of material out of the central regions of galaxy F11119 and into the galactic bulge could help explain this correlation.

“These connections suggested the black hole was providing some form of feedback that modulated star formation in the wider galaxy, but it was difficult to see how,” said team member Sylvain Veilleux, an astronomy professor at UMCP. “With the discovery of powerful molecular outflows of cold gas in galaxies with active black holes, we began to uncover the connection.”

“The black hole is ingesting gas as fast as it can and is tremendously heating the accretion disk, allowing it to produce about 80 percent of the energy this galaxy emits,” said co-author Marcio Meléndez, a research associate at UMCP. “But the disk is so luminous some of the gas accelerates away from it, creating the X-ray wind we observe.”

The accretion disk wind and associated molecular outflow of cold gas could be the final pieces astronomers have been looking for in the puzzle explaining supermassive black hole feedback. Watch this video animation of the workings of supermassive black hole feedback in quasars.

Credits: M. Weiss/CfA

When the supermassive black hole’s most active, it clears cold gas and dust from the center of the galaxy and shuts down star formation in this region. It also allows shorter-wavelength light to escape from the accretion disk of the black hole astronomers can study to learn more. We’ll keep you updated on any additional discoveries.

What’s the conclusion?

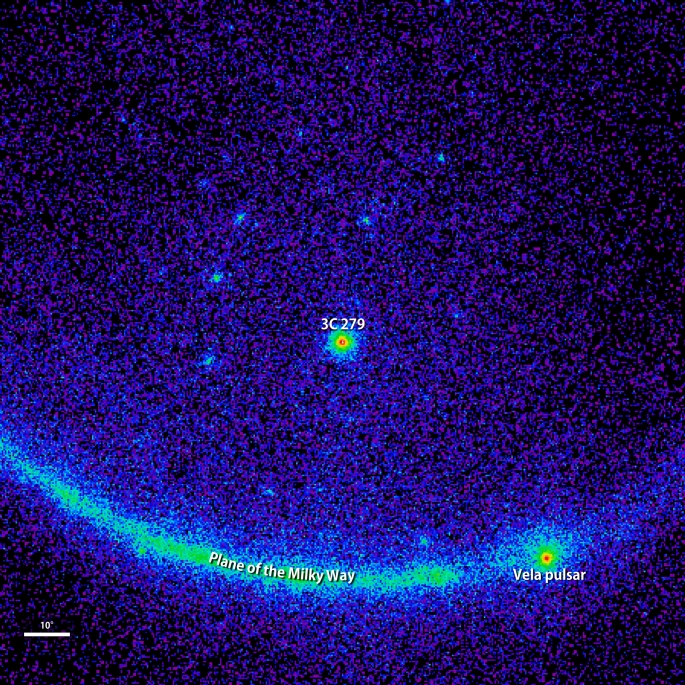

Astrophysicists conclude F11119 could be an early evolutionary phase of a quasar, a type of active galactic nuclei (AGN) with extreme emissions across a broad spectrum. Computer simulations show the supermassive black hole should eventually consume the gas and dust in its accretion disk and then its activity should lessen. Leaving a less active galaxy with little gas and a comparatively low level of star formation.

Credits: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration

Astrophysicists and scientists look forward to detecting and studying feedback mechanisms connected with the growth and evolution of supermassive black holes using the enhanced ability of ASTRO-H. A joint space partnership between Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (ISAS/JAXA) and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Suzaku’s successors expected to lift the veil surrounding this mystery even more and lay the foundation for one day understanding a little more about the universe and its mysteries.

Watch an animation made by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center showing how black hole feedback works in quasars here.

Journey across the cosmos with NASA.

Learn more about the universe you live in with the ESA here.

Read and learn more about supermassive black holes feedback mechanisms.

Read and learn what astronomers have discovered concerning AGN here.

Read more about galaxy IRAS F11119+3257.

Discover ASTRO-H here.

Learn about the discoveries of the Suzaku X-ray Satellite.

Discover Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency here.

Discover NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Learn more about the European Space Agency’s Herschel Infrared Space Observatory here.

Learn what astronomers have discovered about the Monster of the Milky Way.