Exotic ice floes and distinct layers of haze above dwarf planet’s surface

Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Space news (July 29, 2015) – 1.25 million miles (2 million kilometers) from Earth and headed into the Kuiper Belt

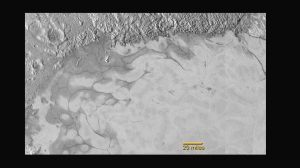

NASA space scientists looking at LORRI images and data sent back to Earth by the New Horizons spacecraft ten days after closest approach to the dwarf planet Pluto received a nice surprise. Exotic ices flowing across the surface of the dwarf planet Pluto as glaciers do on Earth and possibly Mars. Indicating geological activity planetary scientists had dreamed of but didn’t truly expect to find, and the possibility even bodies at extreme distances from the Sun could be crucibles for the ingredients of life.

“We knew that a mission to Pluto would bring some surprises, and now — 10 days after closest approach — we can say that our expectation has been more than surpassed,” said John Grunsfeld, NASA’s associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate. “With flowing ices, exotic surface chemistry, mountain ranges, and vast haze, Pluto is showing a diversity of planetary geology that is truly thrilling.”

“We’ve only seen surfaces like this on active worlds like Earth and Mars,” said mission co-investigator John Spencer of SwRI. “I’m really smiling.”

“At Pluto’s temperatures of minus-390 degrees Fahrenheit, these ices can flow like a glacier,” said Bill McKinnon, deputy leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics, and the Imaging team at Washington University in St. Louis. “In the southernmost region of the heart, adjacent to the dark equatorial region, it appears that ancient, heavily cratered terrain has been invaded by much newer ice deposits.”

Detailed analysis of LORRI images taken of Pluto’s surface reveals a global pattern of ice floe zones varying according to latitude. The darkest surface terrains are found near the equator region, with mid-toned terrains being mainly located in mid-latitudes, and lighter colored terrains covering the North Polar Region.

Mountain Ranges Viewed on Pluto’s Sputnik Planum

Planetary scientists have named the two peaks of the mountain range Hillary Montes (Hillary Mountains) for Sir Edmund Hillary, who along with legendary mountain guide Tenzing Norgay summited Mount Everest in 1953. Rising over 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) above the surface of the planet, image climbing to the top of these peaks, a feat humankind could one day attempt and achieve. This would truly be an inspiring moment during the human journey to the beginning of space and time.

“For many years, we referred to Pluto as the Everest of planetary exploration,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado. “It’s fitting that the two climbers who first summited Earth’s highest mountain, Edmund Hillary, and Tenzing Norgay, now have their names on this new Everest.”

View a video here of a simulated flyover of Sputnik Planum and Pluto’s recently viewed mountain range called Hillary Montes.

Seven hours after reaching its point of closest approach to Pluto, New Horizons looked back at the dwarf planet through its Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) just in time to view sunlight beaming through its atmosphere highlight gasses rising as high as 80 miles (130 kilometers) from its surface. Subsequent analysis of images revealed two distinct gas layers, one at around 30 miles (50 kilometers), and the other at 50 miles (80 kilometers).

“My jaw was on the ground when I saw this first image of an alien atmosphere in the Kuiper Belt,” said Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado. “It reminds us that exploration brings us more than just incredible discoveries — it brings incredible beauty.”

Credits: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

“The hazes detected in this image are a key element in creating the complex hydrocarbon compounds that give Pluto’s surface its reddish hue,” said Michael Summers, New Horizons co-investigator at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia.

Planetary scientists believe the hazes detected in the LORRI images form through a process in which sunlight breaks up methane gas particles, which have been detected in the atmosphere of Pluto. This process leads to the formation of more complex hydrocarbon gasses, like ethylene and acetylene, which have been detected by New Horizons. These heavier compounds fall to the lower regions of Pluto’s atmosphere, where they condense into ice particles that form the hazes viewed. The ice particles are then struck by ultraviolet sunlight, which converts them into the dark hydrocarbons covering the surface of the dwarf planet.

This theory is different than first thoughts on the possibility of this process occurring, in fact, space scientists had previously calculated temperatures would be too warm for such hazes to form above the altitude of 20 miles (30 kilometers). It appears they’ll have to devise a new theory for how the hazes detected could form so far from the surface of Pluto.

Presently around 7.6 million miles (12.2 million kilometers) from Pluto and flying deeper into the Kuiper Belt, New Horizons will continue to send data back to Earth through this year and 2016. All involved in the mission expect to discover more and more about dwarf planets, the Kuiper Belt, and the Solar System as the human journey to the beginning of space and time heads into unseen territory searching for the unknown.

Learn more about NASA’s space mission here.

Learn more about NASA’s New Horizons mission and discover dwarf planet Pluto and its moons here.

Read about NASA’s New Horizons of the Human Journey to the Beginning of Space and Time

Learn about the search for the missing link in black hole evolution

Read about clear skies and hot water vapor detected on Neptune-size exoplanets

8 thoughts on “Pluto Shows Planetary Scientists Geophysical and Atmospheric Surprises”